A Statistical Perspective on Twin Studies

Posted on: June 14, 2022

Post Category: Statistics

What if some of the things you were told were influenced by genetics were not really influenced by genetics?

This blog post will cover the logic behind twin studies, what they attempt to measure/understand, and why they may not be the best type of study to perform when analysing the significance of genetics – from a statistical point of view.

A quick guide to twin studies

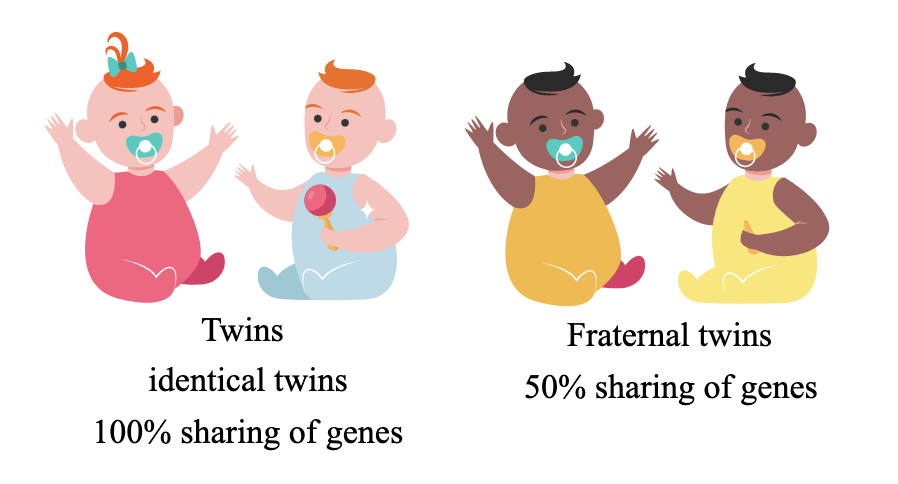

Twin studies are studies that are performed on identical and fraternal (or non-identical) twins, and they aim to measure the significance of genetics on the development of traits and disorders.

So what does a twin study experiment look like? There is a large sample of identical twins and non-identical twins. And the logic is that, if it is observed that a pair of identical twins is more likely be diagnosed with a certain disorder compared to a pair of non-identical twins, then the observation provides evidence that genetics is a significant contributor for the disorder.

However, from a statistical perspective, twin studies are flawed and lead to misleading conclusions. As per the Center of Genetics and Society (2011), twin studies rely on two assumptions: (1) the genetic makeup of (identical) twins are the same and (2) the world treats identical and non-identical twins the same i.e. the “equal environments assumption”. The first assumption is demonstrably untrue, and the second assumption has never been proven. From a statistical perspective, the second assumption is problematic because it ignores confounding factors.

What are confounding factors?

Confounding factors are significant factors/effects that are not measured in an experiment or model.

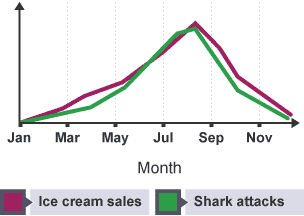

A classic example to illustrate confounding factors is the significant correlation between ice cream sales and shark attacks. When ice cream sales increase, the number of shark attacks increase. Does that mean that ice cream sales cause shark attacks? No. The significant correlation is not because of a causation relationship but there is a confounding factor that links both variables: the temperature.

So, if we were to model the number of shark attacks using ice cream sales, an increase in ice cream sales would correspond to an increase in the number of shark attacks.

BUT if we were to model the number of shark attacks using ice cream sales AND the temperature, an increase in ice cream sales, while holding the temperature constant/unchanged, will NOT increase the number of shark attacks – it will probably also be constant/unchanged.

While both models are correct, the second model better-highlights the underlying factors that cause shark attacks.

Twin studies, and the significance of genes in attention problems and ADHD diagnosis

So, how does this idea of confounding factors translate to twin studies? One of the key underlying assumptions is that identical and non-identical twins experience the same environment. But this is an assumption, not a control in these types of studies.

It has been proven that identical twins do not experience the same environments as non-identical twins. In particular, studies have shown that identical twins spend more time together than non-identical twins – and this makes their environments more similar. This means that identical twins are more likely to adopt similar behaviours and experience similar events in their lives.

So the difference in environments between the two groups is a confounding factor. A twin study may show that a particular disorder may be significantly contributed by genetics, when some of this contribution could be in fact attributed to the environment.

In ‘Stolen Focus’, a book written by Johann Hari, Professor Stephen Hinshaw, a professor of psychology at Stanford University, explained that ’75 to 80 percent’ of ADHD is contributed by genetics.

However, Hari found that these statistics did not come from direct analyses of the human genome, but from twin studies.

Another study used SNP heritability, which is a method that determines how much of a characteristic is genetically driven using genetic make-up. And from this study, it was found that 20 to 30 percent of attention problems were explained by genes.

About the author

Jason Khu is the creator of Data & Development Deep Dives and currently a Data Analyst at Quantium.